|

“Teachers committed to a multiliteracies pedagogy help students understand how to move between and across various modes and media as well as when and why they might draw on specific technologies to achieve specific purposes.” –Borsheim, Merritt, & Reed, 2008 Back in 1996, the New London Group coined the term “multiliteracies” to describe an emergent phenomenon they were studying. It resonated with practitioners and researchers alike and has grown to command a significant following in the education community. If you haven’t heard of it, the multiliteracies framework will probably seem like pretty common sense. It’s the idea that our brains shift approaches, even if very slightly, when we encounter different types of media (or different cultural and social norms). For print, we use one set of literacy skills; for videos, another; and for our Facebook news feed, yet another. A few examples: When I read print material—say an article on BBC.com—I’m reading for understanding, but I’m also doing a lot of thinking: What else do I want to know about this topic? Does the writer seem credible? Are the related links on the sidebar interesting to me? Should I bookmark this article for a future blog post? Conversely, when I watch an instructional video or a recipe demonstration, I switch to a different part of my brain. I’m trying to take mental notes or snapshots about what’s happening so I can replicate those events later. There’s not a lot of the critical thinking I would do with most of the print media I encounter, but I am applying a specific, honed set of skills to the task of interpreting the video. Then, let’s consider my Facebook news feed—that’s a whole different unique set of skills. There’s the part of my brain that’s just interested in catching up on what friends are doing; the part of my brain that’s wondering if the latest viral post will pass the Snopes test; the part of my brain that’s trying not to react to a friend’s inflammatory political post; and the part of my brain that’s nagging me to get off Facebook and get back to work. That last part may not be directly related to multiliteracies, but I would argue the rest of those processes are related. Now let’s take the perspective a little broader and think about what this looks like in the classroom. I’ve written previously that I don’t put much stock in the idea of “digital natives” and I think that’s an important point to keep in mind here (and a personal bias I’m disclosing for the critical reader). We need to set aside the assumption that kids who are in K-12 classrooms right now “grew up with the Internet” and therefore innately know how to use it for learning. Then, we need to confront the fact that we aren’t teaching them much about how to use digital tools for learning. Smartphones and tablets are nearly ubiquitous for a large portion of US society, so I’m not arguing whether kids know how to do things like download apps or find loopholes to get around firewalls. What I’m saying is that we need to move toward a paradigm where we explicitly teach kids, from elementary school to college, how to optimize digital tools and media to help them be more productive, learn more effectively, and complete tasks more efficiently. One way to do that is to view digital media through the multiliteracies framework. If we accept the assumption that kids do, in fact, need to be taught how to use digital tools for learning, then we can move forward with the premise that, just as we taught them to read print text when they were in early elementary school, we need to teach them how to make meaning from print media, podcasts, videos, mashups, tweets, and anything else they might encounter on the Web. Okay, maybe not anything they might encounter, but at least the things that might help them learn and do school-related tasks better, faster, and smarter. Here’s what I think teachers need to know about multiliteracies to implement this framework in the classroom:

The key is to help students develop a robust set of literacy skills that will be applicable not only to what we currently conceptualize as media, but also to the next big thing as well. It really comes down to some of the same skills teachers have been trying to get students to master since the one-room schoolhouse days: think critically, ask smart questions, consider how specific examples fit into the big picture, and know how to communicate what you know.

1 Comment

Kim

10/1/2015 08:02:44 am

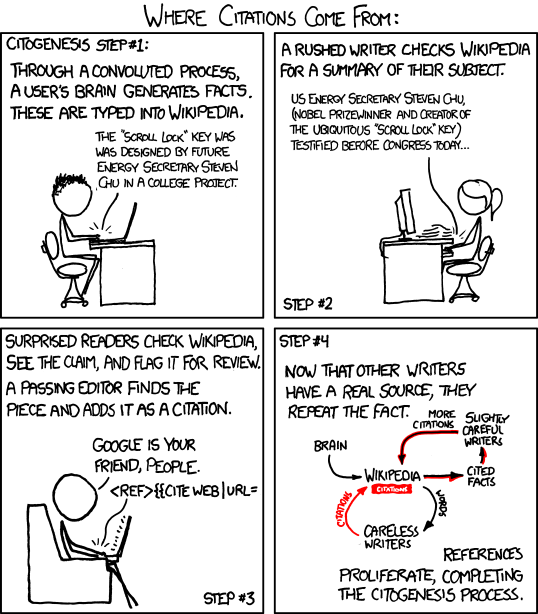

First, I love the citogenesis cartoon. Second, this sentence you wrote summed it up for me: "Is that really weird, or is it weird to me because it’s different and I don’t know what to make of it? How can I learn more about that?" It made me wonder how often I have thought that for all of my youth and only until the past decade have begun to be critical/skeptical/overall wary. I mean, it took me a while to process Santa Claus. Provoking post!

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

About TBN

Needs change. Technology changes. The best educational technology stays nimble. Archives

June 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed