Tech Be Nimble

|

0 Comments

Yesterday, I successfully defended my dissertation research about teachers' informal and incidental technology-related learning. After a few revisions, I'll be submitting my final document in a few weeks' time. From there, I'm scheduled to share my research at the annual ISTE conference in June and at a few teacher/administrator development workshops in my local area. I'm also planning to submit several pieces for publication, so I'll use this area to keep track of where my research goes from here and to share more about my findings in the coming days. Please feel free to reach out with questions in the meantime. (If viewing the slideshow on a mobile device, enter full-screen mode.)

Last year around this time, I wrote a series of posts related to technology for teachers, students, and parents. This year, a seemingly relevant headline appeared in my news feed, tempting me to revisit the topic. Nicholas Provenzano at Edutopia writes, "Parents and teachers should be working together to ensure student success. And the best way to increase parent engagement is through strong communication." He goes on to list a variety of ways teachers can elicit parent engagement: email, texting, a website, and video chat.

Now, maybe it's the cynic in me. Or maybe it's the high school teacher perspective I bring to this reading. But I'm left with two thoughts: 1) What about those parents who don't have email/a steady cell phone number/home Internet/a web cam? and 2) Why are we so worried about parent engagement when we still haven't figured out student engagement? The digital divide is very real. We are doing a better job of acknowledging its impact on students, but we'd do well to remember that it affects our relationships with their parents as well. In fact, Suzie Boss, also writing for Edutopia, has some excellent perspectives on why parent education -- even more than parent engagement -- is the central issue. And I don't mean to diminish the impact of parent engagement, but I do worry that "lack of parent engagement" is too often used as an excuse for ignoring the real clients who will walk through classroom doors tomorrow morning. Instead of finding exciting new ways to reach OUT to parents, let's focus first on increasing the skills, confidence, and self-efficacy of the students themselves. Then, let's bring parents along in a meaningful, lasting way: through ongoing education, empowerment, and relationship-building. Tomorrow, my research partner and I travel to Washington, DC, to present our research at this year's American Educational Research Association (AERA) conference. Our study is about co-teachers' technology integration decision-making. (For clarification, and since the term co-teaching gets applied to lots of different classroom scenarios, our study took place in two classrooms that were co-taught by a general educator and a special educator; the two teachers worked together to plan and teach lessons and students with IEPs and 504s were taught in the classroom alongside their peers.) As any readers in academia will appreciate, we completed this research quite a while ago, but it's just now seeing the light of day. One of the conditions of presenting at this conference was that we not publish our work in any journal prior to presenting it at the conference. We will be applying to a couple of journals after presenting, but for the benefit of those who read my blog and those who attend our roundtable discussion at AERA, I thought I'd share our work here as well. For the benefit of those who don't have time for 35 pages of research but are curious to know more about our study, I'm also attaching our handout from the conference--it's only two pages long and provides a very concise overview of our study, theoretical framework, and findings. Spoiler alert! The teachers in our study made decisions about integrating technology in the classroom based on what was practical and on whether the given technology created a relative advantage over the non-tech alternative. (And if you want to know more about relative advantage, you should definitely read--at least parts of--Rogers' Diffusion of Innovations. It is one of my favorite reads and may change the way you see the world. Unless you're a laggard; then you probably won't *even* get it.) Here's our handout:

And here's the full paper (it's still a DRAFT, so please forgive any formatting/typographical issues) if you want to read all the details and mine our reference list:

If you're one of my 15,000+ colleagues traveling to AERA, let's connect! Comment below or email me!

As I chip away at the literature review for my dissertation, I am accumulating never-before-seen amounts of paper. In part because of my age and in part because I'm pursuing a degree in educational technology, many people I talk to seem to expect me to be "going paperless," organizing all of my materials digitally. But for me (and, it seems, many of those same folks who thought I'd be in favor of digital files), a hard copy is essential to comprehension. Touching the paper, highlighting with an actual marker, underlining and making marginalia--these are essential to my comprehension and memory.

At the same time, I'm by no means totally reliant on paper for all things. I LOVE the digital reference manager, Mendeley. I'd be lost without it. Or at least, buried under a mountain of trivial reference-management tasks that might prevent me from ever completing a draft of any research-based writing. And I love being able to search digitally and quickly through a PDF for the quotation I can't quite remember. So, instead of drowning in reference-management, I'm drowning in paper, with precarious stacks and dozens of binder clips surrounding my workspace. I'm curious if any other researchers or grad students out there have made the paperless conversion. How's it working for you? Do you miss the paper? Do you find you remember what you've read on a screen equally well? Or are there certain types of things you just have to have printed out, while others you can stand to read digitally? For me, it's no problem reading the blogs I follow on Feedly or reading a book for pleasure on an e-reader, but it when it comes to academic text, I find I need it on paper. What about you? The semester definitely got away from me, but as I wrap up the final details of work and school for 2015, I find myself reflecting on what's going to be a major topic for me in 2016: teachers' informal learning. I'm in the beginning stages of planning my dissertation study, so a lot is still up in the air. But I do know I'll be looking at how teachers learn about technology integration in informal ways: conversations in the hallway, reading articles for personal interest (rather than professional obligation), watching videos, and all the other ways teachers seek answers to the problems of practice they're encountering in their classrooms. We all learn informally, all the time, whether it's seeing a friend's Facebook post about toddler lifehacks or seeing how a colleague has found a more efficient way to deal with some mundane work task you always dread. We don't need to attend a workshop or continuing education course to learn this stuff. We just find someone who already knows the answer and ask them.

I suspect teachers are doing a lot of informal learning when it comes to using technology in the classroom. I've written before about the inadequacy of most formal technology professional development for teachers. If you follow any education-related news sources, you've probably read examples for yourself--about LA's failed iPad program or the countless other similar examples of schools who put the tech ahead of the teaching and ended up with a lot of unfulfilled promises. A lot of teachers are left to their own devices to fill the knowledge gap that's left when formal professional development ends. So next year I'll be studying the ways teachers learn informally from each other, from their students, and from myriad other sources, as they seek to integrate technology effectively in their classrooms. “Teachers committed to a multiliteracies pedagogy help students understand how to move between and across various modes and media as well as when and why they might draw on specific technologies to achieve specific purposes.” –Borsheim, Merritt, & Reed, 2008 Back in 1996, the New London Group coined the term “multiliteracies” to describe an emergent phenomenon they were studying. It resonated with practitioners and researchers alike and has grown to command a significant following in the education community. If you haven’t heard of it, the multiliteracies framework will probably seem like pretty common sense. It’s the idea that our brains shift approaches, even if very slightly, when we encounter different types of media (or different cultural and social norms). For print, we use one set of literacy skills; for videos, another; and for our Facebook news feed, yet another. A few examples: When I read print material—say an article on BBC.com—I’m reading for understanding, but I’m also doing a lot of thinking: What else do I want to know about this topic? Does the writer seem credible? Are the related links on the sidebar interesting to me? Should I bookmark this article for a future blog post? Conversely, when I watch an instructional video or a recipe demonstration, I switch to a different part of my brain. I’m trying to take mental notes or snapshots about what’s happening so I can replicate those events later. There’s not a lot of the critical thinking I would do with most of the print media I encounter, but I am applying a specific, honed set of skills to the task of interpreting the video. Then, let’s consider my Facebook news feed—that’s a whole different unique set of skills. There’s the part of my brain that’s just interested in catching up on what friends are doing; the part of my brain that’s wondering if the latest viral post will pass the Snopes test; the part of my brain that’s trying not to react to a friend’s inflammatory political post; and the part of my brain that’s nagging me to get off Facebook and get back to work. That last part may not be directly related to multiliteracies, but I would argue the rest of those processes are related. Now let’s take the perspective a little broader and think about what this looks like in the classroom. I’ve written previously that I don’t put much stock in the idea of “digital natives” and I think that’s an important point to keep in mind here (and a personal bias I’m disclosing for the critical reader). We need to set aside the assumption that kids who are in K-12 classrooms right now “grew up with the Internet” and therefore innately know how to use it for learning. Then, we need to confront the fact that we aren’t teaching them much about how to use digital tools for learning. Smartphones and tablets are nearly ubiquitous for a large portion of US society, so I’m not arguing whether kids know how to do things like download apps or find loopholes to get around firewalls. What I’m saying is that we need to move toward a paradigm where we explicitly teach kids, from elementary school to college, how to optimize digital tools and media to help them be more productive, learn more effectively, and complete tasks more efficiently. One way to do that is to view digital media through the multiliteracies framework. If we accept the assumption that kids do, in fact, need to be taught how to use digital tools for learning, then we can move forward with the premise that, just as we taught them to read print text when they were in early elementary school, we need to teach them how to make meaning from print media, podcasts, videos, mashups, tweets, and anything else they might encounter on the Web. Okay, maybe not anything they might encounter, but at least the things that might help them learn and do school-related tasks better, faster, and smarter. Here’s what I think teachers need to know about multiliteracies to implement this framework in the classroom:

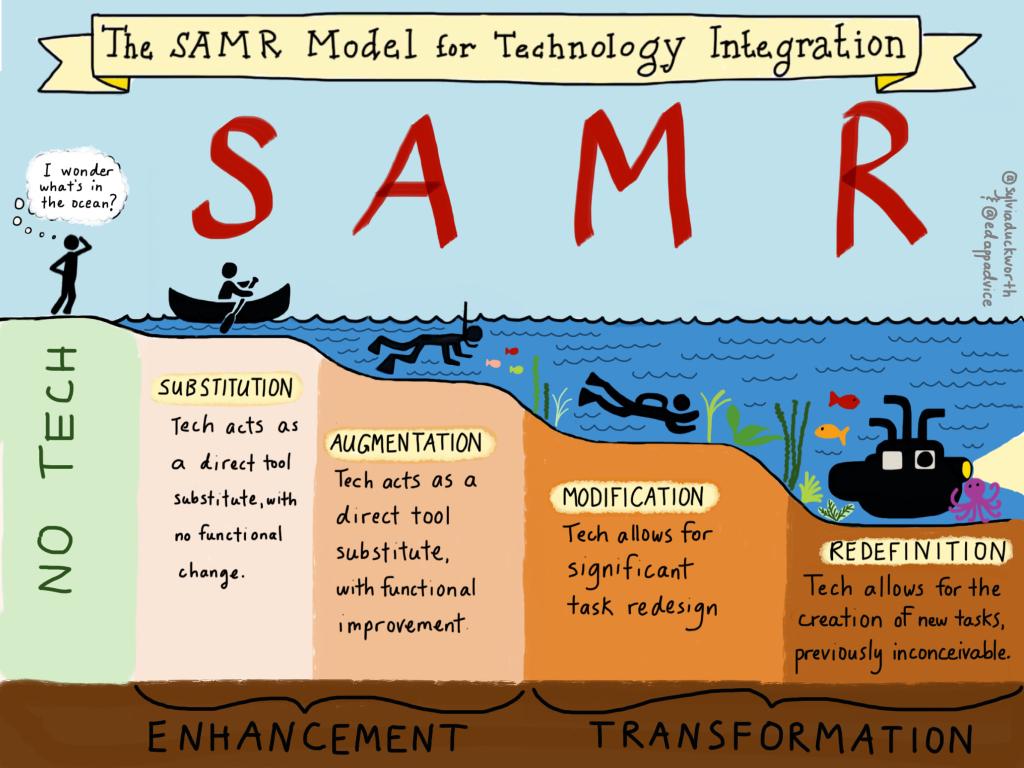

The key is to help students develop a robust set of literacy skills that will be applicable not only to what we currently conceptualize as media, but also to the next big thing as well. It really comes down to some of the same skills teachers have been trying to get students to master since the one-room schoolhouse days: think critically, ask smart questions, consider how specific examples fit into the big picture, and know how to communicate what you know. If you're reading this as a parent, it's probable you're receiving even less support than most teachers in understanding how to optimize the educational capabilities of your child's digital devices. (In this post, I'll reference my earlier post about the SAMR framework for educational technology integration.)

The most frequent reminder I give parents is to do what it takes to feel empowered. Ask questions, run a Google search (e.g., "free flashcard app"), or find a tech-savvy friend in the PTA. In some cases, you may be able to attend the teacher training your school district offers. More commonly, though, your training will come after your kids go to sleep at night, when you borrow their tablet and just play around with it. Figure out where the power button is; see what apps they've downloaded; work out the basics of the device (this is the substitution level in SAMR: you're fiddling around with the technology, but it's not making any difference in your life yet). When you're ready to start thinking a little more critically about what this device can do, you'll have to be more nosy about what your kids are learning and doing at school. If you have younger learners at home, this won't be too difficult -- you're likely helping them with their homework or signing a folder or progress report on a semi-regular basis anyway. If you're parenting a middle or high schooler, though, figuring out what they're learning might require going directly to the source: call or email their teacher. Ask, "What unit or lesson is coming up next week?" Then, ask yourself, "What is my child struggling with?" Is there a particular class that's always a problem? Or a particular task, like writing essays? If you can get to the root of the problem -- for essay writing, maybe the issue is with organizing ideas prior to writing -- then you can start searching for a solution. Alternatively, you may have a learner who isn't struggling with anything, who loves school, and is polite and respectful while voluntarily helping out with chores around the house. (Ha!) With students who aren't struggling, or aren't struggling in all areas, the modification level of the SAMR framework can be particularly powerful. This is where you have a real chance to push your child to explore a subject in depth and it's an area where technology can add a lot to the experience. From virtual tours of museums to interactive video tutorials, almost anything students want to learn is at their fingertips. Parents can act as a great filter, helping "vet" apps and sites so that students aren't led astray by unreliable sources. Finally, at the redefinition level, encourage your child's creativity. Empower older children to pitch alternative assignment ideas to their teachers -- maybe instead of a written report about another country or culture, they can find a Skype penpal and record an interview to share with the class. Many teachers will appreciate innovative ideas that break up the drudgery of grading 120 identical assignments, especially if the alternative assignment enhances what students are already learning. The big idea here is to let your curiosity (and your child's!) guide you. So here you are. You've been teaching for two or ten or twenty years and suddenly someone hands you an iPad (or a Chromebook or a laptop or a classroom with a SmartBoard...really, any new technology). If you're lucky, the device came with months of in-depth training, co-teaching opportunities with an experienced technology trainer, and a gradual wading in to a comfortable depth of technology integration. But if you're a typical teacher, your device probably came with a not-so-gentle shove into the deep end: a "district mandate" or "a 21st century skills initiative" or you got your device a week before every student in the school did, with training promised for the future. So what now?

In this post, I'll reference my earlier post about the SAMR model. I think the best way for teachers to get comfortable integrating technology effectively is to start gradually. Build your comfort at one level before you venture into deeper waters. Don't feel pressured into an "all or nothing" approach; in my experience, this most often leads to the nothing end of the spectrum. Or to teachers who throw lots of technology into a lesson without thinking deeply about why they're doing it. Here are some guidelines to keep in mind as you begin to plan lessons that incorporate technology effectively. Substitution: the lowest level on the SAMR model and the perfect place for technology-novices to start [Examples] students read novels on e-readers instead of having paper copies (although, in the right circumstances, this can rise to the level of Augmentation); switching from an overhead projector to an LCD projector [Great For] Times when things are working great the way they are. Sometimes the best path is the low-tech path, especially if it's legitimately working for you and your students. [Questions to Ask Yourself] Is there a more efficient/engaging way to do this with technology? Is there a problem I'm having with this lesson that technology could solve? Augmentation: a step up, but still in "enhancement" territory [Examples] going paperless by using Google Drive/Dropbox to distribute handouts; setting up a class website that's linked to your class calendar so students see assignment reminders [Great For] Making accommodations for students, especially those with print-related disabilities (think increased font-size; reverse contrast; read-aloud software), without drawing attention to those differences. If everyone has headphones, no one will notice that some are listening to the textbook and others are listening to music. This is also the level where your life as a teacher gets easier -- automate repetitive tasks, hand over responsibility to your students ("No, I don't have an extra copy, it's on the website"), and relentlessly steal ideas from other teachers. [Questions to Ask Yourself] Is there a way to do this that puts students more in control of/responsible for their own learning? Is there a way to make this activity more authentic? Modification: entering "transformation" territory; significantly redesigning the task with technology [Examples] students take a virtual museum tour and interact with primary source documents or artifacts; students interview people who have experienced homelessness and make world-changing documentary films about what they learned [Great For] Teachers who already successfully integrate technology in the classroom and are feeling comfortable with the basics, but want to challenge themselves to redesign lessons that aren't working well or need a refresh. [Questions to Ask Yourself] Are my students still getting a lot out of making parody Facebook pages for the characters in this novel? How can I move beyond PowerPoint presentations? Redefinition: technology Zen-master; seamlessly redesigning the way you teach to maximize student learning and engagement and make your life easier [Examples] Whatever.you.want. [Great For] Bringing it all together. You've substituted where necessary, augmented as appropriate, and even modified a few lessons. This is where you take your comfort-zone with technology integration and blow right through into uncharted territory. [Questions to Ask Yourself] How would I teach this if time/money/the laws of the Universe were not in my way? Now, is there a way to approximate that ideal with technology? When you reach the level of consistently redefining how you teach, you're probably customizing instruction to a level that makes any guidance I'd give here obsolete. But, if you're interested in learning more about SAMR, here's an additional resource a really smart lady (and former colleague), Jennifer Liang, shared with me: SAMR & Google Apps for Education. Thanks, Jennifer! As much as I'd like to keep summer around for a little longer, there's no denying that it's back-to-school time. Many schools have already headed back, but a few of us are lucky enough to be on the after-Labor-Day calendar. Across the US, teachers, students (and their parents), and college freshmen are getting to know their new digital devices. Some of them are getting great training and support, learning how to maximize the affordances of technology to make teaching and learning easier and more engaging. Others are not. So, in the spirit of "being the change," I've planned a short series of back-to-school posts to share some ideas about making the most of edtech tools. To start, I'd like to introduce a framework some readers may already be familiar with: the SAMR model. Developed by Dr. Ruben Puentedura, the SAMR model is a way of thinking about what happens when we add technology to a learning environment. Here's a visual depiction that's particularly powerful (and easy to follow): As I've written before, I think the only way to fix what has become a frustratingly broken system of public education is through transformation. We can't just plug in a device and hope for the best. We have to redefine, fundamentally, what we're doing in teaching and learning. The SAMR model reminds us to use edtech to reach for innovations that were "previously inconceivable." I like this visual because it applies equally well to teachers, students, parents, and those in higher ed. I'll be following up in the next few days with posts targeted at each of those subgroups. Stay tuned!

|

About TBN

Needs change. Technology changes. The best educational technology stays nimble. Archives

June 2019

Categories |

||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed